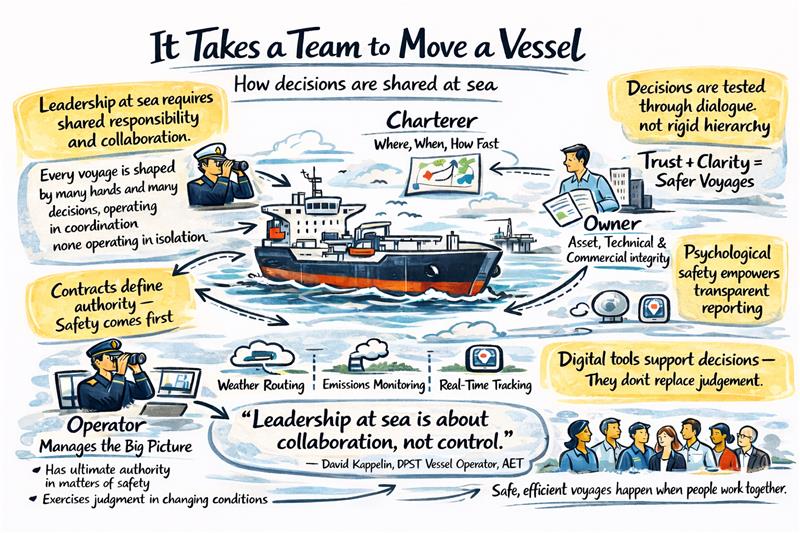

When people think about a vessel’s voyage, they often picture one person in charge; usually the captain on the bridge. In reality, every voyage is shaped by many hands and many decisions, made across sea and shore.

That is especially true in complex offshore operations, where safety, commercial priorities and technical realities must constantly be balanced.

To shed light on how this works in practice, the AET Corporate Communications Team spoke with David Kappelin, a DPST Vessel Operator at AET.

There is no single person in charge

“A safe voyage doesn’t happen because one person makes all the decisions,” Kappelin said. “It happens when everyone understands their role and respects everyone else’s.”

A vessel’s voyage is influenced by several key roles:

- The master, who has ultimate authority over safety and navigation

- The charterer, who provides commercial voyage instructions under the charter party

- The owner, who is responsible for the asset and its integrity

- The operator, who coordinates the commercial and operational picture day to day

Each role brings a different perspective with none operating in isolation.

Coordination is the real work

A voyage is rarely just about sailing from one point to another.

Port calls, agents, pilotage, weather routing, emissions performance, crew changes and offshore schedules must all align, often across different time zones and organisations.

Local agents manage port arrangements. Technical managers oversee the vessel’s condition. Charterers issue voyage instructions. Operators sit in the middle, ensuring information flows smoothly and risks do not escalate.

It is a constant balancing act and one that depends heavily on trust.

Contracts define authority, but safety comes first

Commercial authority is clearly set out in contracts, particularly under time charter arrangements. Safety, however, is never negotiable.

If conditions change or risks emerge, the master has the right, and responsibility, to act.

That balance is deliberate. It ensures decisions are tested, discussed and grounded in experience, rather than made in isolation.

Digital tools support decisions, not judgement

Modern vessels generate vast amounts of data, from weather routing to fuel consumption and emissions monitoring.

This visibility helps teams make better and more informed decisions. It does not mean ships are controlled from shore.

Human judgement, experience and dialogue remain essential, particularly in complex offshore environments.

Leadership at sea looks different today

For Kappelin, good leadership is about

- open communication

- shared accountability

- people feeling safe to speak up

- learning from experience, both your own and others’

That mindset is critical in DPST operations, where precision, coordination and trust underpin every transfer. “It really is not about hierarchy,” he stressed.

Why this matters

Oil producers rely on dynamic positioning shuttle tankers, or DPSTs, to safely transport crude from offshore fields to shore, often in demanding conditions.

Behind every successful operation is not just technical capability, but disciplined decision-making, clear roles and strong collaboration across organisations.

For more than a decade, AET has worked closely with producers across Brazil, the North Sea and the Barents Sea through our DPST operations. Today, we are one of the world’s top three DPST operators, owning and operating one of the youngest and largest DPST fleets serving these regions.

Click here to learn more about AET’s DPST operations.